The Crimean War provides history too many unfortunate milestones. It's rightly considered the first modern war, a dress rehearsal for the scope and scale of World War I, at a time when the romance of the Napoleonic wars was still within a generation of experience. A few battles apparently equaled the Somme for the human toll, at least in terms of the rate of lives lost. Mortar fire was so ubiquitous, some learned to slept through it in the trenches, with explosions raining down all around them.

For the first time, news came from the front on a wire, introducing a new level of tactical precision, logistics and immediacy. The first professional war correspondents and press took advantage of this immediacy, allowing the public to follow along with the changing tides of their soldiers' fortunes. The press and public reaction start to play a more prominent role in directing the course of war policy during this conflict.

Yet despite all these unfortunate milestones, the Crimean War remains a forgotten history for many, overshadowed by the wars of the 20th Century. Filling in this blank space led me to Figes' text. If asked about the Crimean War before reading this, there's not much I could have said apart from a strong guesstimate that 'Crimea' figured prominently.

For the first time, news came from the front on a wire, introducing a new level of tactical precision, logistics and immediacy. The first professional war correspondents and press took advantage of this immediacy, allowing the public to follow along with the changing tides of their soldiers' fortunes. The press and public reaction start to play a more prominent role in directing the course of war policy during this conflict.

Yet despite all these unfortunate milestones, the Crimean War remains a forgotten history for many, overshadowed by the wars of the 20th Century. Filling in this blank space led me to Figes' text. If asked about the Crimean War before reading this, there's not much I could have said apart from a strong guesstimate that 'Crimea' figured prominently.

|

| Sevastopol, reduced to rubble by hundreds of thousands of cannon shots. |

Bad intelligence and a tactical error prevented the French, British and Ottoman forces from quickly taking the port city, leading to a 2 year siege that cost countless more lives - from the ever-present exchange of mortar fire, and mix of poor preparation with the elements. While not quite saving the Russians as they did against Napoleon, the famous 'Generals January and February' did exact an incredible toll on British troops, and on morale overall. The French fared much better, with the famous Zouaves (crack troops of their time) setting the standard of excellence and bravery. The Ottomans were widely mocked by both allies and enemies for their cowardice. One anecdote in the text refers to some English and Russian troops sharing a smoke during a truce to clear out the dead and injured from no-mans land, which I'll quote from here:

1st Russian Soldier - "Englise bono!"

1st English Soldier - "Russkie bono!"

2nd Russian Soldier - "Francis bono!"

2nd English Soldier - "Bono!"

3rd Russian Soldier - "Oslem, no bono!"

3rd English Soldier - "Ah, ah! Turk no bono!"

1st Russian Soldier - "Oslem!" Making a face, and spitting on the ground to show his contempt.

1st English Soldier - "Turk!" pretending to run away, as if frightened, upon which the whole party go into roars of laughter, and then after shaking hands, they all return to their respective beats.

There's a lot to unpack from a scene like this. In fact, the religious angst between Roman Catholic/Protestant and the Russian Orthodoxy is a root cause of the conflict, overshadowing (for the moment) contempt for the Muslim Ottomans. The Ottoman troops get a bad rap, I think. Fleeing in the face of the enemy is as much the result of lacking interest in supporting an unpopular home-government and poor provisioning/armament as it is real cowardice. The Russians themselves faced widespread desertion by its own serf-based troops, who were often falsely promised (or implied) freedom if they took a turn at the front (even while others showed remarkable bravery in holding out at Sevastopol).

Florence Nightingale, and The Charge of the Light Brigade are perhaps the two best known products of the Crimean War. A young Lieutenant Tolstoy, stationed at Sevastopol during the war, also had plenty of fodder for future writing, with the experience having a profound influence on his politics and art.

|

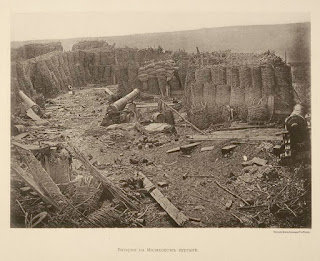

| A Russian redoubt, complete with earth-filled wicker baskets called 'gabions' used to defend against enemy fire. |

In short, this is a great history, and one well presented by Figes. Highly recommended.

No comments:

Post a Comment